|

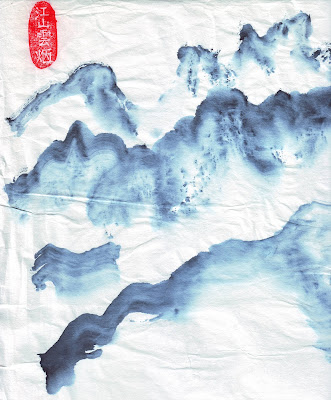

| At the Great Wall, Watercolor, brush and rice paper, Lucey Bowen, 2005 |

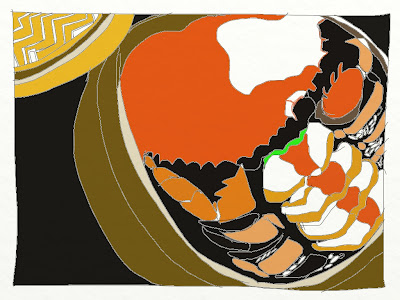

Nina Simond's "Shanghai Food Lover's Guide" served to remind us that the a quarter century had passed since the end of the Cultural Revolution. It seemed that in spite of Irene Corbally Kuhn's fears, Shanghai was once again the "Paris of the East," at least for foodies. Simonds provided a recipe, and the trick (aspic) for making the irresistible Shanghai Stuffed Soup Buns.

Other things have changed, along with the magazine's graphics and layout. A Chinese restaurant in London would never have been written up in the early days; this issue reviews four. There's even a review of the Asian-inspired food in Minneapolis, at the Walker Art Center's 20.21 Restaurant.

The centerpiece of the April issue was "The Man Who Came to Dinner." No less a writer than Calvin Trillin described celebrating, at

Chez L'Ami Louis, in Paris, the 70th Birthday dinner of R.W. Apple,

New York Times correspondent and food critic. I mention this because Trillin arranged to be served, the night before, a dinner including four kinds of dumplings, served up by an emigré chef, Yang from Shandong.

The indomitable Caroline Bates returned with a survey called "When Tokyo Met Lyon, Or the Rise and Rise of Asian Fusion." She dated the birthplace of Asian Fusion to 1982, locates it at the Sheraton La Reina at LAX, and credits its emergence to chef Roy Yamaguchi, Japanese born and of Japanese and Hawaiian parentage. The father, long unacknowledged was, of course, "Trader Vic" Beregeron. The next phase was the melding of French

cuisine minceur and Japanese

kaiseki. Next came Wolfgang Puck, serving up franco-japanese, but calling it Chinois. In New York, she wrote, what had been a West Coast style was adopted by European trained chefs like Gray Kunz and Jean-George Vongerichten. In 2005, she sensed a return to West Coast roots. "The show goes on."

Harris Salat's essay on the aesthetics of Japanese ceramics and food described a difference kind the fusion, a sensual one. Fuchsia Dunlop and Michael Roberts described the opposite: encounters with the unfathomable, the different. In "Culture Shock," Dunlop recounted the results of introducing three outstanding Chinese chefs, from Sichuan, to American food at Thomas Keller's The French Laundry in Yountville, California. Conclusion: Chinese chefs found American food and dining customs just as strange as American found Chinese. Chef Michael Roberts' journey had a different outcome. Faced with a debilitating disease, he traveled to South India, and was inspired by the spiritual, introspective patience of its cooks.

My journey in 2005 was closer to Roberts'. One child had left for college. The other was traversing the rocky terrain of finishing high school. I was unsure of my own future. In a year I would be sixty years old. Both my parents had died in their mid-sixties. I felt old and growing older.

Occupying my mind with strange and wonderful art and literature of Asia filled the emptiness, the feeling of purposelessness. With my new-found-awareness of Hindu and Buddhist beliefs in the afterlife, I joked that as I might not come back as a sentient being, if I wanted to learn Mandarin, I had better start now. And so I did. And when a brochure for a tour showed up in the mail, I wanted to go. Dick could only take time away from work for the last leg of the trip, from Shanghai to the Yellow Mountains. I redoubled my study of Mandarin.

The trip surprized me. The itinerary of palaces, temples, museums, and archeological sites was overwhelming. My classes and my reading were too new for me to absorb the historical context of what I was seeing. My enjoyment came from self-discovery, from being more myself.

A Chinese artist, Xu Bing, who lives half the year in Beijing and half in Brooklyn, observed that he understands himself better for living in the United States. Traveling in China, I felt my truest self. Everywhere we went, I painted. I painted the mountains from the Great Wall, the desert from the back of our bus, the misty cliffs of the Yangtze from my cabin on a cruise boat, ancient towns from park benches, the dreamy mountains of the River Li from a river boat and the Yellow Mountains from a rocky perch. The act of painting drew people to me and I made rudimentary conversation in Mandarin. At the end of the trip, I happily gave away many of the paintings to my fellow travelers. The act of observing the landscape, and painting to capture my impressions, had filled me with energy. Buying brushes, ink and paper, I felt united with China's visual history.

My body was my other concern. I tried to swim everywhere we went, and in the larger cities, our hotels had pools. And I got massages. In China, massage is a medical treatment, and sometimes is accompanied by moxi-bustion and acupuncture. I will never forget receiving this treatment, gazing out the porthole as we floated down the Yangtze. Food? You must remember that this was a tour-group!

New York:

Café Gray at Time Warner Center, 10 Columbus Circle is still

Café Gray.

66 at 241 Church Street is closed.

Spice Market at 403 West 13th Street is still

Spice Market.

Vong at 200 East 54th Street is closed.

Yumcha at 29 Bedford Street is closed.

Los Angeles:

Beacon at 3280 Helms Avenue, Culver City, is closed.

Chaya Brasserie at 8741 Alden Drive, Beverly Hills, is still

Chaya Brasserie.

Chaya Venice at 110 Navy Street, Venice, is still

Chaya Venice.

Chinois on Main at 2709 Main Street, Santa Monica, is still

Chinois on Main.

Matsuhisa at 129 North La Cienega Boulevard, Beverly Hills is still

Matsuhisa.

Orris at 2005 Sawtelle Boulevard, West Los Angeles is still

Orris.

Roy's Woodland Hills at 6363 Topanga Canyon Boulevard, Woodland Hills, is still

Roy's.

Trader Vic's at the Beverly Hilton, 9876 Wiltshire Boulevard, Beverly Hills is still

Trader Vic's.

Yujean Kang's at 67 North Raymond, Pasadena is still

Yujean Kang's.

Minneapolis:

20.21 at the Walker Art Center, 1750 Hennepin Avenue